WASHINGTON (RNS) Enter the “Religion in Early America” exhibit and there are objects you expect to find: Bibles, a hymnal and christening items.

But on closer inspection, a broader picture of faith in the Colonial era emerges: a Bible translated into the language of the Wampanoag people, the Torah scroll of the first synagogue in North America and a text written by a slave who wanted to pass on the essentials of his Muslim heritage.

[ad number=“1”]

“Religion in early America was not just Puritans and the Pilgrims, and then the Anglicans and the negotiation of Christian diversity,” said Peter Manseau, curator of the exhibit that opens Wednesday (June 28) at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

“It was a much bigger picture. It was a story of many different communities with conflicting, competing beliefs, coexisting over time with greater and lesser degrees of engagement with each other.”

RELATED: State of the art: A Q&A with the Smithsonian’s new religion curator

A church bell display at the “Religion in Early America” exhibit in Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History/Jaclyn Nash

The yearlong exhibit, part of the museum’s “The Nation We Build Together” series of exhibitions, demonstrates mostly through material objects the range of religious expression from Colonial times through the 1840s.

The gallery that recounts religious freedom, diversity and growth is bookended by two large physical depictions of religious life.

Peter Manseau is curator of American religious history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Photo courtesy of Peter Manseau

On one end is an 800-pound church bell crafted by revolutionary rider Paul Revere in 1802 that hung for three decades in a Unitarian Universalist church in Maine and later was used to call factory workers to a textile mill in North Andover, Mass.

“Ministers would say, ‘I know that I can find a better sounding bell if I import one from Europe but because I’m a patriot, I’m going to buy a Paul Revere bell,’’’ said Manseau, author of the exhibit-related book “Objects of Devotion: Religion in Early America.”

At the other end of the exhibition space is a foldable pulpit used in the fields of the English Colonies by evangelist George Whitefield in the First Great Awakening of the 1700s.

RELATED: 300 years after his birth, Whitefield has staying power with evangelicals

“It’s a representation of the changing forms of worship in America that then transformed the nation,” Manseau said of the growth in denominations such as Methodism, which had more than 18,000 churches by 1860. “This was a new way of experiencing religious devotion, a very emotionally driven way, sort of a carnival atmosphere — religion as spectacle rather than something endured through long Puritan sermons.”

[ad number=“2”]

Also on view: a Boston-based evangelist’s translation of the Bible into the Algonquian language of the Wampanoag people, creating what became the first published Bible in the U.S., with hopes of converting Native Americans. Manseau said it was used mostly so colonists could say to people back in England “look what’s possible for converting native America if you continue to fund our missions.”

The Mid-Atlantic region display of the the “Religion in Early America” exhibit at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History/Jaclyn Nash

Harvard Divinity School scholar Catherine Brekus, an expert on the history of religion in America, said it’s appropriate for the exhibit to reflect the range of religions that existed in early America.

“We tend to think much more about the Pilgrims but in fact the original 13 Colonies were really very religiously diverse,” including “lots of different Native American religions,” as well as Catholics, Jews and Muslims. “The middle colonies — Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Maryland — were the most religiously diverse in early America and most linguistically diverse too.”

Beyond traditional Protestant life, the exhibit depicts what it calls the “flowerings of religious devotion,” as well as objects influencing faith found already existing when the Pilgrims arrived.

On display are a 1654 Torah scroll from New York’s Congregation Shearith Israel, a page from the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon and the iron cross believed to be fashioned from the ships that brought the first English Catholics to Maryland.

Some scholars estimate that 20 percent of African-born men and women were followers of Islam before they were transported as captives.

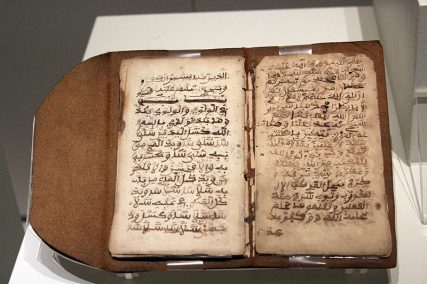

A 13-page Arabic document written by Muslim slave Bilali Muhammad in the 19th century. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

A 13-page Arabic document written by Bilali Muhammad in the early 19th century reveals the efforts of a man who lived on Sapelo Island, Ga., to leave a legacy of his Muslim faith. Considered the only known religious text written by a Muslim slave in the U.S., it includes passages from the Quran as well as details on the basics of Islamic practice — from the times of prayer to explanations for washing hands and feet before praying.

“What it seems to be is a document written by someone who is in the process of forgetting a language and trying to remember it,” said Manseau. “It seems that, on this remote island plantation where he lived, he was making an effort to pass along his beliefs and practices to the following generation.”

In contrast, just a step or two away from that small volume is a portrait of Omar ibn Said, a slave jailed in Fayetteville, N.C., after an escape attempt who wrote Arabic verses on his cell with a piece of coal. He converted to Christianity after being sold to a prominent Presbyterian family.

[ad number=“3”]

“He becomes, in a minor way, kind of a media figure in the 19th century,” said Manseau of a time when stories of his conversion in the Southern Christian press placated fears sparked by a recent Muslim slave revolt in Brazil. “They point to him as basically the good Muslim who abandoned Islam for Christianity.”

The exhibit also includes numerous examples of how faith was lived outside of houses of worship and within homes.

There is an 1820s playset of 45 Noah’s Ark figures and a children’s book from the mid-1800s that begins with “A is for Adam.” And there’s a silver bowl from the home of Virginia patriot George Mason.

A Noah’s Ark playset from the 1820s, when many children were allowed to play with “Sunday toys.” RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

“George Mason might throw a party and chill his wine glasses in this bowl but then the next day, or the next Sunday, would christen his children in this bowl,” said Manseau. “There was no separation. There was no sense that one was profane and one was sacred.”

About half of the objects, such as Thomas Jefferson’s 1820 unorthodox version of the Bible and George Washington’s christening robe from 1732, are part of the Smithsonian’s collection, and some have appeared in past exhibitions. The rest — such as African Methodist Episcopal Church founder Richard Allen’s candlesticks and hymnal and Rhode Island founder Roger Williams’ compass and sundial — are on loan.

RELATED: AME Church founder honored with postage stamp

The exhibit, which closes June 3 next year, is part of a larger initiative by the museum to feature religion in a variety of dimensions, including theater and musical presentations. Manseau, who wrote “One Nation, Under Gods,” said future exhibits are planned that will focus on how religion intersects with other aspects of evolving American culture.

“Religious liberty was not immediate,” he said. “It was not inevitable. It was born of very practical concerns by practical people trying to create a new nation and a new way of thinking.”