DURHAM, N.C. (RNS) — In the three years since Charles Horry was released from prison, he has come to realize that being out doesn’t mean doing things on your own.

“You can’t do it alone,” he said. “You have to have God on your side.”

And maybe a little help from your friends.

On Thursday (April 25), Horry stood before about 150 people gathered in the sanctuary of a Presbyterian church at a celebration thrown for former prison inmates called a Reentry Homecoming. Talking about how he had reached his three-year milestone, Horry credited, in addition to a county agency that provides peer counseling, substance abuse treatment and job training, his “faith team.”

“They showed me so much love,” Horry said.

This week, a Bureau of Justice Statistics report showed that the number of people held in American prisons declined again in 2017, continuing a trend that began in 2009.

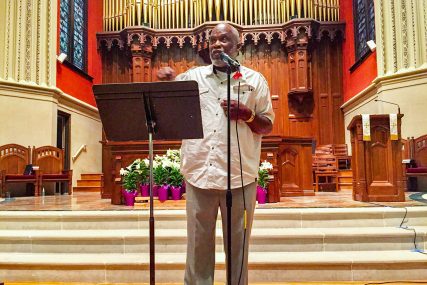

Charles Horry tells his life story at a ‘Reentry Homecoming’ celebration at Durham, N.C.’s First Presbyterian Church on Thursday, April 25, 2019. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

But as inmates are being released from prison — 22,000 inmates are released from North Carolina’s state prison system each year alone — states, cities and municipalities are recognizing the need to provide services to help people reenter society if they are to remain out of prison.

In Durham County, whose core is this city of some 267,000 people, the need is being answered in part by the Religious Coalition for a Nonviolent Durham, which works with the county’s Criminal Justice Resource Center to match former inmates with a five-member faith team like Horry’s. The team offers them support and friendship beyond the usual social services, as well as an opportunity to develop that most critical of social skills for former prisoners: relationships.

The coalition currently fields 20 faith teams, each of which has signed one-year covenants with a former inmate to meet twice a month for one year. The teams — organized through the city’s churches and synagogues — don’t offer financial support. They’re there to give advice and encouragement on how to navigate life’s challenges outside prison walls.

The Durham coalition has so far paired 100 former inmates with volunteer faith teams since the project began in 2003. A total of 28 of the region’s houses of worship, including Baptists, Episcopalians, Methodists, Presbyterians and Quakers, in addition to Catholic and Jewish congregations, have organized such teams.

“The idea behind the faith teams is to create a sense of community and to create a place where returning citizens are loved, because everyone deserves love, compassion and belonging,” said Drew Doll, reentry coordinator for the coalition.

The 20 faith teams took on only a minuscule fraction of the 743 “returning citizens” Durham absorbed last year, but their mission is not to reach them all. Faith teams are paired only with those who have been incarcerated for a long time and have few or no family members and no real social support.

They are people like Horry, 67, who had spent most of his adult life in prison. At Thursday’s celebration, he recounted how “this is as long as I’ve ever been out of prison,” and he beamed with pride describing his job as manager for a franchise of Buffalo Wild Wings.

Sitting in the front pew at Thursday’s homecoming at First Presbyterian Church in downtown Durham was Wilbert Pipkin, also 67, who was released two years ago after serving a total of 36 years.

A former heroin addict, he now lives in a recovery house and spends much of his time preaching the good news of the city’s reentry efforts.

Wilbert Pipkin spent 36 years behind bars. After getting out, he received help from a faith team. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

That first year after he was released, Pipkin said, faith team members called him every day to check on him, drove him to doctor appointments and lifted him up one night after he relapsed.

“Normally, when I get high one time, that’s it; it’s over,” he said. “But through them encouraging me and showing me so much love I was able to get (back) on the path.”

The effort is based on the so-called Circles of Support and Accountability model, or CoSA, which is used around the country and in Canada to help reintegrate formerly homeless families as well as sex offenders.

The idea is that such circles can help reduce a person’s likelihood of reoffending, a theory that in the coalition’s 16-year history has been shown to be true. Whereas North Carolina’s three-year recidivism rate is about 40 percent (though the re-conviction rate is lower), coalition Director Ben Haas said only 15 percent of former inmates who completed the one-year faith-team commitment were re-arrested or jailed.

The faith teams are not intended to proselytize, and the coalition ensures former inmates are matched according to belief or nonbelief. Some teams spend their time together cooking; some play the dice game Yahtzee; others read and discuss books, said Doll.

Most meet for a meal.

Dale Herman, a retired volunteer on his second faith team, said the benefits run both ways.

“It’s an education for all of us to learn what it’s like coming out of prison and broaden our perspectives about what life is like for a lot of people in society,” said Herman, 76, a resident of Durham. “It’s good for us to understand what the systems are doing to our society.”

Besides helping former inmates individually, the coalition and many of its volunteers have advocated for the “ban the box” campaign, a national initiative aimed at removing the check box on job applications that asks if applicants have a criminal record. (The city of Durham has banned the box for city employees, but most private companies in the city have not.)

Others support bond reform and an end to money bail, which forces people who have been arrested to pay money to secure release before trial.

Mark-Anthony Middleton, a city council member who attended the homecoming celebration, said he was glad to support city conservation initiatives, such as planting trees and buying electric buses. But helping integrate former inmates, he said, was just as important.

“If we’re not conserving opportunities,” he said, “our conservation is for naught.”