(RNS) — Stacey Abrams, the former Georgia House minority leader who lost a razor-thin race for governor in 2018, voted on Thursday (Oct. 15), driving her ballot to a local drop box.

Jeanine Abrams McLean, a former biologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who now helps her sister run the census advocacy group Fair Count, also took advantage of Georgia’s early voting, wearing her “Come to Your Census” T-shirt to her polling place in Tucker.

In an interview with Religion News Service, Stacey Abrams called it a coincidence that the siblings had cast their votes on the same day. The family’s pastor, the Rev. Ralph Thompson, said voting is ingrained in the Abramses. “The family is just a tight-knit cadre of people who understand that it is incumbent upon them to vote and to make a difference,” he said.

Thompson, whose predominantly Black Columbia Drive United Methodist Church in Decatur, Georgia, has a sign outside that says “Vote Early,” said the entire family has long viewed voting as “a sacred civil duty.”

Hundreds of people wait in line for early voting in Marietta, Georgia, Monday, Oct. 12, 2020. (AP Photo/Ron Harris, File)

When Abrams, 46, threw herself into her twin causes of protecting the right to vote and being counted in the census, most news stories attributed her efforts to her loss in the gubernatorial election by 50,000 votes to Brian Kemp, the state’s top elections official at the time.

Abrams, charging that Kemp suppressed votes, announced the formation of her voter access organization, Fair Fight, in her concession speech, along with her intention to sue Kemp for running what she alleged was an unfair election. (The suit is ongoing.)

But Abrams also connects voter protection and other civic activism to her family’s faith.

“My faith is central to the work that I do, in that I not only hold Christian values, but my faith tradition as a Methodist tells me that the most profound demonstration of our faith is service,” said Abrams.

Abrams and her siblings were raised by two United Methodist clergy, the Rev. Robert Abrams and the Rev. Carolyn Abrams, both now retired. Their parents trained them early in service, bringing them to work at soup kitchens and to boycott a local Shell gas station to protest its corporate owner’s connections to apartheid-era South Africa. McLean was an acolyte, or altar server, and Stacey Abrams said she “did double duty” as an usher and a choir member in the small church her family attended at the time.

The Rev. Carolyn Abrams, left, and the Rev. Robert Abrams, right, at Columbia Drive United Methodist Church in Decatur, Georgia. Photo courtesy of Ralph Thompson

“You look at Stacey, who’s doing public service with all of her advocacy,” said McLean, 38. “You look at Fair Count and the work that I’ve been able to do here, but even public service working in public health: My siblings are all doing some sort of work that has an impact on people’s lives because that’s just the way that we were taught. … The first place we learned to do that was in the church.”

The family has continued to pursue its commitment to public service through the church, using faith as a motivator to be engaged in politics. “I was raised to not only think about my faith as an activity, but to translate that into how I engage community,” said Abrams.

RELATED: Black church turnout effort mobilizes against alleged voter suppression

Jeanine Abrams McLean takes a selfie that she posted on social media with a reminder for people to complete the 2020 U.S. Census. Photo courtesy of Jeanine Abrams McLean

Earlier this year, Fair Count provided a “faith app” to dozens of congregations to help clergy text their members with census and church information. McLean envisions faith leaders encouraging congregants to get involved when new maps for redistricting are reviewed in their communities.

Apps that can be used on mobile phones make such information more available to disadvantaged communities, where cell phones are more widely available than broadband-dependent devices.

“What we’re trying to do is provide these resources, not only to help to make sure that there is long-term power building in faith communities in these vulnerable areas,” McLean said, “but also to just give people a lifeline so that they can continue to reach out and stay connected with their members.”

McLean worships at Thompson’s Columbia Drive Church in Decatur, along with her husband and two children and Robert and Carolyn Abrams. Stacey Abrams attends when her schedule allows and has been a speaker for special events and obliges her pastor’s impromptu invitations to make remarks.

Abrams’ four other siblings are Leslie Abrams Gardner, a U.S. District Court judge; Andrea Abrams, an anthropologist and an associate vice president for diversity affairs at Centre College in Kentucky; and two brothers, Richard Abrams, a Georgia social worker; and Walter Abrams, a detox tech at a California drug treatment facility.

All but Gardner joined McLean, Stacey Abrams and their parents on a Facebook “Abrams Family Reunion” as Fair Count held a virtual event to highlight census participation in the Magnolia State where they were raised.

Members of the Abrams family participate in a Facebook virtual event for Fair Count in Sept. 2020. Video screengrab

Voting activism and the Black church have long been mutually reinforcing, as churches historically provided a protected space to discuss politics and organize drives. The family has been that for the Abrams as well.

In a January speech to law students at Chapman University in California, Gardner recalled her grandmother’s story of being taught at her Mississippi church how to pass a written poll test, only to be refused the vote because she didn’t get the “right” answer when asked how many bubbles there were in a bar of soap.

“She told me she made sure once she finally got the right to vote that she exercised it on every occasion,” Gardner said. “As we celebrate the progress we’ve made, we must remain resolute to continue the fight for equal rights and equal justice under the law.”

RELATED: Black churches, via phones and Facebook, bridging digital divide amid COVID-19

The Abramses are helping to expand the focus on the vote to other areas they say are equally empowering. “There are three pillars of democracy — the census, voting and redistricting — and we want to make sure that communities that have been left out of all three of these conversations have their voices heard from now and into the future,” said McLean in an interview.

“I evaluated the census the same way I did the right to vote or the right to read,” said Robert Abrams on the Facebook event, sitting next to his wife. “Anything that anyone worked so hard to keep from you must be good.”

Stacey Abrams speaks to the congregation of Columbia Drive United Methodist Church in Decatur, Georgia. Photo courtesy of Ralph Thompson

Perhaps the most important link between Abrams and her church background, however, has been the resilience it has granted her to come back from seemingly overwhelming setbacks. The latest came Tuesday, when the Supreme Court decision ended the extended census count, a decision McLean called “jarring.”

“I hope my witness is always seen as one of perseverance,” said Abrams. “I may not have been the governor, but that didn’t absolve me of the responsibility that my faith tells me I hold, which is to ensure that the marginalized, the voiceless, the disadvantaged, are able to be heard and to be served.”

Religious messages have been a part of Abrams’ campaigns dating at least to her run for governor, when her “Boundless Belief” ad featured her recollections of the Saturdays of service observed in her parents’ home as a child and included footage of her holding hands around a dinner table with family members as an adult.

Speaking earlier this year at Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Selma, Alabama, Abrams referred to the biblical book of Isaiah’s discussion of faithful endurance when she spoke of civil rights marchers who fought and bled for the right to vote on Bloody Sunday in 1965.

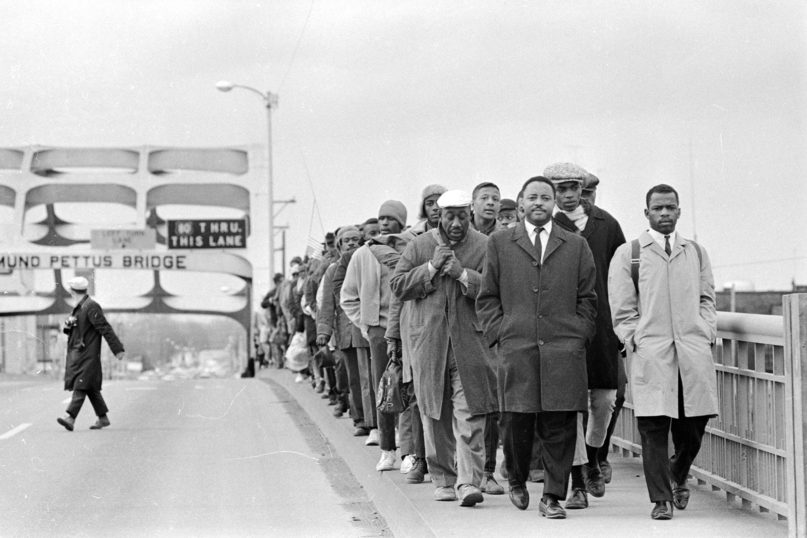

John Lewis, far right, and fellow marchers cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge, on Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965, in Selma, Alabama. © Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group. Photo by Tom Lankford, Birmingham News

“I’m the product of the Voting Rights Act, an act that was bought and paid for on Edmund Pettus Bridge with foot soldiers who had believed that they had the right to be there,” she said in footage of the event in “All In: The Fight for Democracy,” a 2020 documentary about barriers to voting.

“They stood up and they crossed the bridge. Those were the wings of the eagles that Isaiah talked about. It may have looked like feet crossing the bridge but that was flight.”

Political scientist Andra Gillespie at Emory University in Atlanta said it’s not unusual for Black politicians like Abrams to include faith in voter mobilization work. But her deep experience in congregational life gives Abrams a level of familiarity to draw on more than a few oft-heard Bible verses.

RELATED: Black church leaders push for census participation despite coronavirus

“She’s not going to go to the same places that everybody usually goes to because they only know a handful of Scripture,” said Gillespie, an expert on African Americans and politics. “She’s been around church her whole life, so, yeah, she’s fluent in the Bible.”

Abrams said she’s going to keep up her message despite the disappointments along the way.

“In this country, democracy is how we speak to those in power and how we determine who holds power,” she said. “And that’s my mission.”

This story was supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.