(RNS) — A dispute over a proposed change to a 1990s-era federal law has landed one of the nation’s largest evangelical adoption agencies in the middle of the “woke” wars.

A recent report from Grand Rapids, Michigan-based Bethany Christian Services suggests making changes to the “Multiethnic Placement Act.” Known as MEPA, the 1994 law bars adoption agencies or foster care programs that take government funds from “delaying or denying the placement of a child based on their race, color or national origin.”

While well-intentioned, the law hurts children of color, Bethany argues, by requiring a “colorblind” approach to adoption.

“We’re not saying there needs to be some type of ‘woke’ test,” said Cheri Williams, senior vice president of domestic programs at Bethany. “What we are saying is, it’s very harmful to children to go into this situation with a colorblind philosophy.”

Williams said the recent report was prompted by conversations with adoptive parents and adult adoptees in the wake of the death of George Floyd.

“We heard an outcry from Bethany families saying, ‘we don’t know how to talk about race with our child,’” she said.

Among the families looking for help were Bob and Sally Schmid, a white couple living in the Chicago suburbs. They have two adoptive children; one was born in Ethiopia and the other was born in China, and the racial reckoning that followed Floyd’s death really hit home.

“I don’t think anything could have prepared us for last year,” Bob Schmid said.

Schmid admitted it has been hard for him to talk about race with his kids. First and foremost, they are his kids and he loves them dearly. So he doesn’t always think about how the world sees them differently.

That’s something he has been working on. For support, Schmid said he and his family got help from Bethany. They also turned to their church. Some folks, he said, tried to be supportive. Others were not so understanding.

“Some people would just really push back hard and turn it into a political issue,” said Schmid, whose family has moved to a more diverse church in Chicago. “And that was really very discouraging.”

RELATED: Black children in foster care need relief from systemic racism too

Nathan Bult, senior vice president of government affairs at Bethany Christian Services, said when it was first passed in 1994, MEPA permitted adoption and foster care agencies to consider the best interest of a child before placing them with a foster or adoptive family. That included the child’s race or ethnicity, the adoptive parent’s race or ethnicity, and whether an adoptive parent of one race was prepared to parent a child of a different race.

That “permissible consideration” was taken out of MEPA in 1996.

This Aug. 23, 2018, photo shows the Bethany Christian Services headquarters in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Bethany is one of the nation’s largest adoption agencies. (AP Photo/Paul Sancya)

According to Bethany’s report, the Black children they serve had the lowest rate of reunification with their families. Most Black children adopted through Bethany are placed with white families, and the agency can do little to help those families “preserve Black children’s cultural heritage.”

Naomi Schaefer Riley, an author and resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, argued Bethany is more concerned about being “anti-racist” than caring for children.

“They want people to feel bad about transracial adoption,” Riley, who has been critical of Bethany, told Religion News Service in an interview.

MEPA, she told RNS, has made it easier for Black children to be adopted by prohibiting discrimination, not training. “There is nothing in the MEPA that prevents people from having conversations about race, she said.

Bult, a former Trump administration staffer, said Bethany is not trying to reverse MEPA, but the agency believes the law should return to its original form, with the permissible consideration language restored. He also said Bethany remains fully committed to transracial adoption.

RELATED: Bethany Christian Services to allow LGBT couples to foster, adopt

The Nohe family learned quickly upon adopting their children Nicholas and Rachel, that being a transracial family was something they hadn’t been prepared for. Courtesy photo

Kris Nohe, a writer and consultant in Virginia, said she and her husband had very little training in transracial adoption when their children Nicholas and Rachel, who are Black, came to live with them. The couple called a Black friend for some advice about bath time.

The friend, Nohe recalled, told her to hold off until she could come over and lend a hand.

“That was our first introduction into ‘this is going to be different,’” she said.

Some friends and neighbors were supportive. Others were not. Having Black children, Nohe said, made her aware of how much she did not know.

“You’re going to need to step out of your comfort zone and face issues you’ve blissfully been allowed to ignore,” she said.

Nicholas Nohe, who is 18, said he always knew his parents had a different skin color than he did. But he didn’t realize those differences mattered, at least to the outside world, until he was about 10. Some of his friends didn’t think his parents were his “real parents,” and he felt he had to prove he belonged in his own family at times.

Today, he said, things are better. But still, there are reminders he is different from his parents and his white brothers.

“It’s still a struggle for me,” he said. “Just going to restaurants, where I’ll take my brothers out to eat and they’ll always try to seat them first. We’ll have to say, ‘no, we’re actually all together.’”

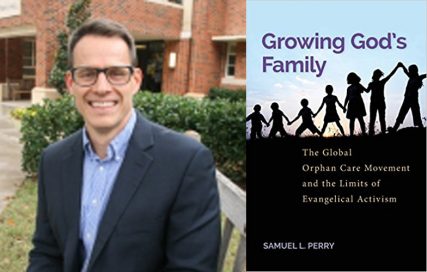

University of Oklahoma sociologist Samuel Perry interviewed hundreds of adoptive families for his 2017 book “Growing God’s Family,” which looks at evangelicals and adoption. Most of the families he spoke with, Perry said, did not take a “colorblind approach” to issues of race.

Samuel Perry and the cover of his book “Growing God’s Family.” Courtesy images from University of Oklahoma Dept. of Sociology & Amazon, respectively

Perry, who grew up in a family with two adopted Black sisters, said in recent years that evangelicals have become more aware of the need for open discussions about the role race plays in adoption. Children need love and stability, he said, but they also need to know about how race affects the world.

Those discussions are often pragmatic, he said, rather than theoretical or ideological.

“What they are talking about is the reality of driving while Black on a Thursday or being followed around in the grocery store,” he said.

RELATED: Despite multiracial congregation boom, some Black congregations report prejudice

Thais Carter, a consultant from Princeton, New Jersey, said conversations about race are a normal part of every life in transracial adoption. Carter and her husband, Heath, a Princeton Theological Seminary professor, have three boys, including their son Isaiah.

“There’s no hiding the fact I didn’t give birth to Isaiah,” she said.

Melissa Busby, an adoptive mom who is married to a pastor, said learning about racial issues is one of “the most loving things” a parent in a transracial family can do.

“Sometimes as Christians, we think good intentions, love and prayers are all we need,” said Busby, who has two adopted children from Uganda. “But good intentions don’t always make for good parenting.”

Transracial families are often reminded the world is not colorblind.

Chalonda and Sidney Dwyer of Kalamazoo, Michigan, have found themselves having to explain their family to outsiders. The Dwyers, who are Black, have three young white children.

RELATED: Dissent from Traditional Plan dominates United Methodists’ top court meeting

That has led to a lot of stares and questions. At times, Chalonda Dwyer said, people assume she is the babysitter.

“Well, actually,” she tells them, “they are mine.”

The Dwyers, who are Seventh-day Adventists, said when they first set out to adopt, they were asked if they preferred children who were Black.

“Being Christians, we felt strongly God was going to send us the right kids,” she said.

The Dwyers said becoming parents to three children at the same time was a challenge. Their three kids, who are biological siblings, were placed with them in 2016, and they have all learned from each other.

Love and their faith have sustained them, said Sidney Dwyer. He and his wife would encourage any family who hopes to adopt to consider transracial adoption.

“Sometimes people look at us like, ‘why are they calling you Mom and Dad,’” he said. “That doesn’t really bother us because our kids love us and we love our kids.”