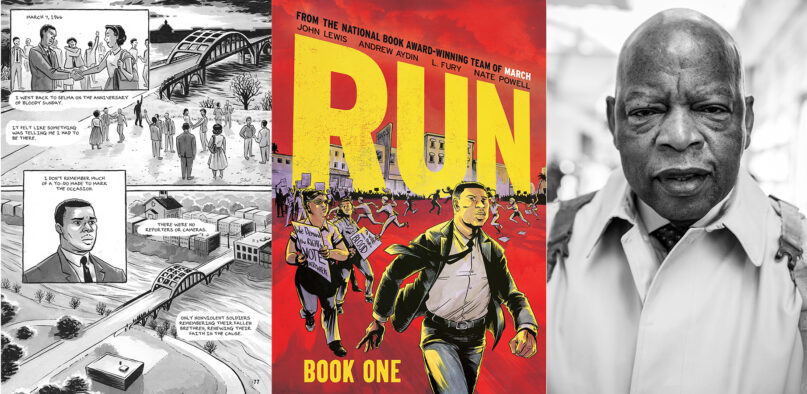

(RNS) — Famed congressman John Lewis once told his then-campaign worker Andrew Aydin how a comic book depicting the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. played a key role in raising awareness about the civil rights movement. Decades later, Lewis and Aydin teamed up to create the award-winning “March,” a graphic novel trilogy.

Now, Aydin is helping shepherd “Run,” co-authored with Lewis, who died last year, and an artistic team. The new graphic novel, releasing Tuesday (Aug. 3), continues the story of “March” after voting rights legislation was adopted but not welcomed by all.

Aydin, a white Christian with United Methodist roots, was Lewis’ digital director and policy adviser and is co-founder of Good Trouble Productions, which produces nonfiction graphic novels.

Andrew Aydin. Photo by The 1Point8

“In this book we ask the question: Is America ready to share its bounty with people of color?” said Aydin, who wrote his Georgetown University master’s thesis on the 1957 comic book about King.

“I think if you look at this through a religious lens, it is long overdue that America should share its bounty with all people, including and most specifically people of color, who’ve been left out and left behind for too long.”

Aydin, 37, talked to Religion News Service about the message of “Run,” what he learned from Lewis and the role of the faith community in continuing voting rights activism.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

It has been just over a year since the death of John Lewis, who was your mentor, your boss and your friend. Is there a key moral or spiritual lesson from him that you continue to carry with you?

The lesson I hold with me most from John Lewis and his life and his example is that you have to be persistent. You have to keep pushing and pulling. You have to keep working ’cause the struggle never ends. We’re only shepherds of it during our time.

RELATED: John Lewis, ‘March’ team talk about faith and civil rights

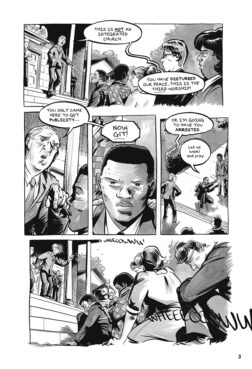

The book opens with a scene outside a church two days after the Voting Rights Act was signed into law in 1965, with John Lewis and other protesters seeking to worship at a white church in Americus, Georgia. What did that timing show?

A page from the “Run” graphic novel. Courtesy image

Opening the book two days after the signing of the Voting Rights Act, at a protest in Americus, Georgia, in which John Lewis was arrested, is meant to show how fast the pushback was to the progress, how slow the implementation of these laws was at that time and continues to be. That just because you had a law on the books didn’t mean the struggle was over, didn’t mean change had happened.

The civil rights protesters were met by a Ku Klux Klan leader who declared, “The Klan is the only salvation of the white man other than Jesus Christ.” How would you compare John Lewis’ approach to the intersection of race and religion with that of the Klan members?

I think the Klan frequently perverted the teachings of Jesus Christ, particularly the New Testament, to their own purposes to manipulate people. And it’s unfortunate. John Lewis was a devotee of the social gospel, of the gospel Dr. King preached. It’s important to understand this conflict because we’ve seen it continue to play out in our politics, in our religious communities throughout the country up to today, and it’s no doubt going to continue. I think you hear sometimes people misquoting Scripture for their own ends. There’s an all-too-often occurrence of cloaking themselves in religion as the means to deflect from the sinister motives.

The book tells of the death of Episcopal seminarian Jonathan Daniels and the attack on then-Catholic priest Richard Morrisroe in Lowndes County, Alabama. John Lewis expresses his frustration that “the white supremacist power structure continued to be willing to murder in cold blood” to halt voting rights of Black people. Did he have an answer for how to counter that?

It gets back to the central conflict. It is incredibly difficult to separate the pain of seeing Black and white bodies beaten, murdered and killed because of what they believe in and because of the fight for equality. And that can hurt people’s soul. It can cause them to become bitter, and it can cause them to become hostile. John Lewis was always trying to keep people together. He would say, “Don’t get down. Do not become lost in a sea of despair. Be hopeful. Be optimistic.” That’s why this book is dedicated to the preachers of hope. Because the only way to survive, the only way to succeed is to maintain that discipline and that hope and that optimism. Because it’s the only thing that’s worked.

As John Lewis eventually withdrew completely from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, how did his faith help him manage the rejection from a movement he described as having been his family?

“Run” cover. Courtesy image

John Lewis was raised and trained in the Baptist tradition. And part of that is understanding you will face good days and bad, you will be tested, you will have to endure if you want to succeed and if you want to help people.

The book illustrates the role of religious leaders in the fight for voting rights in the 1960s. How do you compare that work to the involvement of faith leaders in the new battles over voting rights occurring today?

The movement was led by reverends and ministers, and they’re a model for what faith leaders can do today to guarantee every citizen the right to participate equally in the democratic process. If you’re going to be a moral leader of your community, if you’re going to be a faith leader in your community, that means you have an obligation to ensure each person is counted, each person has a voice, each person is treated as a valuable equal human being, with all the rights and privileges that come with it.

Like John Lewis, you express hope in achieving the beloved community he long sought. How long do you think that will take and do you ever doubt it will be achieved?

I believe it will be achieved. But it may take a lifetime. It may take many lifetimes. This is the perpetual struggle, and even if it is achieved that does not mean the struggle is over, because then you have to protect it. We’ve seen that same struggle with the Voting Rights Act. Just because it was passed and reauthorized in a bipartisan way many times over since, sections have been struck down, it’s not been reauthorized, we can’t get new legislation through the Congress anymore. When we think about that in the context of the beloved community, it’s the perfect example, because even if we do achieve it tomorrow, it does not mean the struggle is over. That means it’s only begun a new chapter.