(RNS) — The three-year anniversary of the Tree of Life shooting in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh on Wednesday (Oct. 27) will include an outdoor memorial service at Schenley Park, with 11 trees planted to remember those slain.

The 11 who died when an armed intruder entered a building housing three Jewish congregations and started firing indiscriminately have been eulogized and written about widely.

Journalist Mark Oppenheimer decided to explore how the Squirrel Hill community responded.

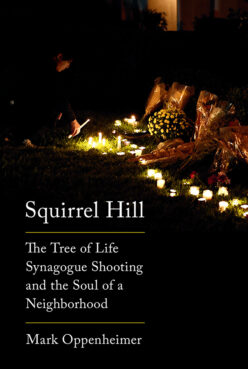

His new book, “Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood,” takes a probing look at how the neighborhood, home to 26,500 people, including 13,000 Jews, coped in the aftermath of the tragedy.

Squirrel Hill, as Oppenheimer writes, is “the oldest, most stable, most internally diverse Jewish neighborhood in the United States” — older than the Jewish suburb of Newton, Massachusetts, or the Chicago suburb of Skokie, Illinois.

Jews began moving there after World War I and, for the most part, have never left. The neighborhood includes multiple synagogues catering to a wide variety of Jewish traditions and a host of other nonprofit supporting institutions, all within 3 square miles.

Mark Oppenheimer. Photo by Lotta Studio

As Oppenheimer writes, “probably no place in America was better positioned to endure (mass murder) than Squirrel Hill.”

The host of Tablet magazine’s podcast, “Unorthodox,” Oppenheimer draws moving portraits of many of the neighborhood’s compassionate and community-minded members who provided a bulwark to the isolation and anomie gripping many other parts of the nation.

RELATED: 3 years after Pittsburgh synagogue attack, trial still ahead

But as the chapters unfurl, starting with the attack and concluding with its first anniversary, he also includes sketches of the “trauma tourists,” including multiple American Jews from elsewhere who tried to intrude on the community in the weeks after the shooting, insisting only they knew how to properly bury the dead and provide comfort for the grieving.

Religion News Service spoke to Oppenheimer about his book ahead of the three-year anniversary, which he was flying to Pittsburgh to attend. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Your family grew up in Squirrel Hill. But you did not.

Right. I’m from Springfield, Massachusetts. But my dad and his father and grandfather all lived in Squirrel Hill. Two generations before that (my ancestors) lived in Pittsburgh but it was before Squirrel Hill was built. My father left for college and never lived there again.

So what drew you to write a book on Squirrel Hill?

First, I’ve always had a strong interest in religion and it’s something I’ve written about ever since graduating from college 25 years ago. Second, I’ve also had a very strong interest in neighborhoods and how neighborhood topography and demography functions to create community. This seemed an opportunity to look at how a neighborhood under stress responded and what sorts of resources it had because of its nature as a close -knit neighborhood with a lot of multigenerational families and social capital. Third, I do have family there and it’s where my dad is from.

On the whole, it seems the people and institutions of Squirrel Hill did a pretty good job attending to the needs of the survivors and victim families, right?

Yes. The community had a lot of affirmative resources for making sure that victims’ families and survivors got the support and the attention they needed. The second thing to consider is the absence of some of the terrible aftereffects you see in communities that have suffered mass killings. In some communities there’s a lot of acrimony among survivors’ families. In some communities, there are suicides of people who survived. There can be a lot of traumatic fallout. Squirrel Hill seemed to do better in terms of keeping people well in the aftermath.

Tree of Life is an aging congregation. It may not survive 10 or 20 years from now. Yet now they’re renovating parts of the building and have hired a renowned architect, Daniel Libeskind. Will the rebuilt space be a museum to the past?

There is concern among some people in Squirrel Hill that a rebuilt Tree of Life building will not get as much use as people hoped for.

Why was the disposition of the building so difficult?

“Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood” by Mark Oppenheimer. Courtesy image

There’s a lot of disagreement over what the right thing to do is with a building that has a violent history. In most countries, they don’t destroy those buildings; in America we do. There were many options. They could sell the building. They could try to remodel the building. They could use it again. They could raze it or sell it. All were live options.

What makes this community so distinct and why do Jews stay there?

There was a very intentional decision in the 1980s and 1990s to renovate and rebuild the communal buildings rather than relocate them — the day schools, the Jewish Community Center, the Jewish Home for the Aged, the Jewish Federation. In many, many metropolitan areas, these core institutional buildings moved to the suburbs as soon as some Jews started moving to the suburbs. In Pittsburgh, there was a very conscious decision made by community leaders to raise money to keep these core institutions in Squirrel Hill. Along with the tenacity of the Squirrel Hill neighborhood already, and the general willingness of so many Jews to stay in the city, having those buildings there made it really, really viable.

You note that Squirrel Hill was known for not wanting to politicize the shooting or make a bold statement on gun control, like the students at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, did. Would you describe it as a more conservative community?

There were definitely people for whom this was political. There was a strong faction that did use the shooting as an opportunity to push for stronger gun laws. The City Council passed such a law but they knew it would be overturned because gun laws in Pennsylvania are state law. There have also been residents who had been very vocal about not wanting the alleged killer to get the death penalty. In the end, if the people who were a bit more quietist ended up having more sway that’s because they were a slight majority among the survivor community of those killed. It wasn’t evidence of greater conservatism than, say, in the Parkland community, but evidence that the victims were an older group of people. The survivors were also older. There was a more measured sense of how to balance the internal needs of the community with a desire to create external change.

You close the book noting that the archivist at a Jewish history center has now begun attending New Light Congregation as a Torah reader. Have Jews become more religiously active? Have they rushed back to support institutions that, for the most part, are declining across the country?

I think it’s too early to tell whether there will be heightened support for institutions. I definitely saw a lot of revitalized commitments among individuals. But their new commitments did not always involve a lot of institutional connection. I saw people learning to chant Torah. I talked to someone who converted. I talked to someone who began wearing a yarmulke. I talked to a lot of people who started taking on some additional level of observance. But there’s no evidence that the membership roll of Tree of Life swelled. Typically you would see two dozen people there, which is pretty much in keeping with before the shooting. It’s very hard to know what those conflicting trends mean for Squirrel Hill or American Jewry 10 years down the road.

What’s been the reception to the book?

I’ve gotten a lot more notes of gratitude than notes of criticism. Everywhere I go to speak, the Pittsburgh diaspora comes out to see me. They came because they are from Pittsburgh and now live elsewhere but feel connected to Pittsburgh. Oftentimes, they will find each other after the talk and find out they have friends in common.

RELATED: Survey: One-third of Jewish college students have experienced antisemitism