(RNS) — Let us read responsively.

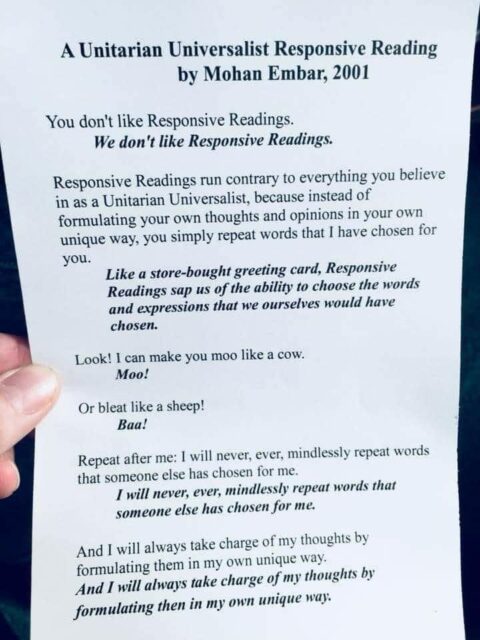

Rabbi: Did you see that Facebook meme going around?

Congregation: Which Facebook meme?

Rabbi: The one about responsive readings.

Congregation: Oh, you mean the parody of Unitarian Universalist responsive readings?

Rabbi: Right. That one.

Congregation: Yes. Did you think that it made a good point?

Rabbi: Yes. I have something to confess to all of you.

Congregation: And that would be … ?

Rabbi: I have never liked responsive readings.

Congregation: Really? Never?

Rabbi: OK, well, maybe at summer camp.

Congregation: May we confess something to you as well?

Rabbi: Go ahead.

Congregation: Frankly, we have never liked responsive readings either.

Rabbi: Wow. Who knew?

Congregation: Well, consider yourself informed.

Rabbi: Why don’t you like them?

Congregation: Because they make us feel like automatons. You could say anything and then get us to say anything, and it would not matter how insipid it was.

Rabbi: Do you really think so?

Congregation: Sure. Try us.

Rabbi: OK. Hmm, well … OK, here goes. “It is incumbent upon us to fight injustice anywhere in the world … ”

Congregation: ” … except if it makes us uncomfortable doing so.”

Cantor (chiming in): Wait. Is that in the liturgy?

Congregation: Yes, it’s right here on the Zoom slide.

Cantor: Darn. You’re right.

Congregation: Also, a lot of these responsive readings are prose, and they don’t lend themselves to responsive reading very well. Just because you break up a paragraph …

Rabbi: … doesn’t make it a prayer, does it?

Congregation: Nope.

Interlude with some soft piano music to calm everyone down.

Congregation: How did this whole responsive reading thing start?

Cantor: I am glad you asked. Certainly, responsive readings are native to ancient Jewish liturgy. Many psalms were chanted antiphonally.

Congregation: Of course! We do that with Ashrei.

Rabbi: Exactly. We “loaned” that practice to the ancient Christian church. In some liturgical traditions, they would alternate verses when they chanted.

Cantor: When we say kaddish, it serves as a responsive reading as well. The reader starts, and then the congregation responds: Amen.

Congregation: You’re totally right.

Rabbi: We also do this with Mi Kamocha — “Who is like You, O God?” Because that is the Song at the Sea, and it might have started as an antiphonal chant between Moses, Miriam and the people of Israel.

Congregation: Isn’t that in this week’s Torah portion?

Rabbi: Yes. In Black churches, they take the antiphonal reading even further. When the preacher is giving a sermon, the congregation will typically shout out spontaneous responses.

Congregation: Can we try that here?

Rabbi: Not. In. This. Lifetime.

Congregation and cantor: You’re no fun.

Rabbi: I admit: There is something cheesy in the way many synagogues and churches do responsive readings. They seem forced and inauthentic. We want worshippers to own their worship, and to live inside the words, and not merely be passive. But, the whole responsive reading thing — it can be grating.

Congregation: We are so glad to hear you say that. Is there a way to fix this?

Cantor: Sure. We can revive the art of congregational singing, which in a time of COVID, is a real challenge. We can create new opportunities for antiphonal singing. We can concentrate our antiphonal energies on those elements of worship that are, and perhaps “always” were, authentically responsive.

Congregation: Sounds good to us. Maybe change it from “responsive” reading to “responsible” reading.

Rabbi: Can we work on this together?

And they all say: Amen.