(RNS) — Celebrating the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday in any year reminds all justice-loving and justice-seeking people of the challenges we face and of the unfinished business of economic inequality, political exclusion and cultural humiliation — the tripod of institutional racism in our racialized society and world.

But this year brings particular pain. At the same time that we seek to bring healing and equity and inclusion to our world, there are many who are violently and vehemently opposed to these goals and seem to be becoming more sophisticated and more militant in their efforts to block and reverse the progress of the civil rights movement. The enemies of justice are more prominent and persistent than ever.

As we remember King, the national news is focused on the indictments of insurrectionists who sought to overturn an election and on the resistance to overturning a Jim Crow-era relic — the filibuster — in order to protect voting rights. We’re hearing that amid a revived pandemic, a significant constituency in our country is demanding the right to be agents of death and disease. We read that a conservative Supreme Court is set to maintain the backward trend in civil rights and human rights.

Anyone seeking to sustain progress toward justice and equity in our society need only read King’s speeches, sermons, letters and essays, written 60 and 70 years ago, to find still, with chilling precision, analyses of the wrongs of our moment.

RELATED: Black faith leaders’ proud legacy on civil rights should include LGBTQ rights

An unfortunate consequence of the national holiday — a holiday I celebrate seriously and energetically — is the very narrow and sanitized version of King that is presented in the sound bites of memory we see.

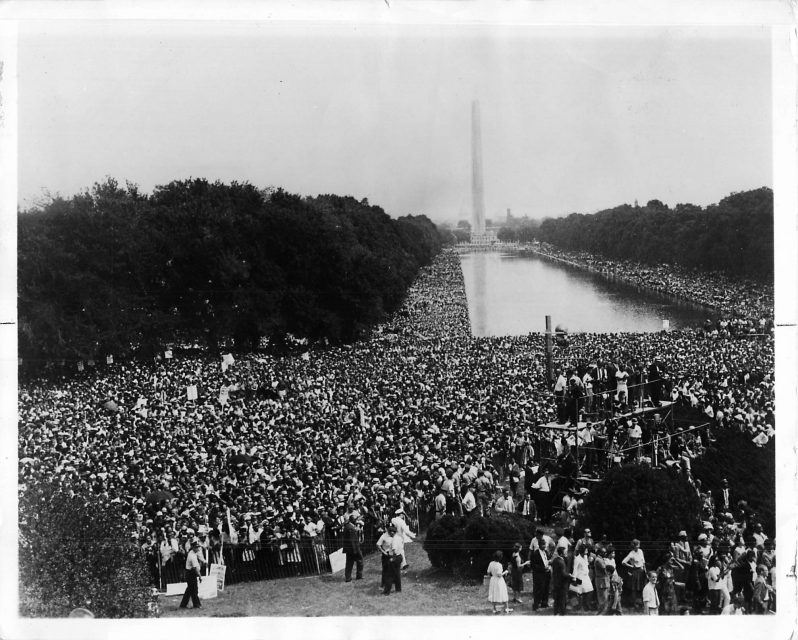

Writing in The New Yorker, journalist and historian Jelani Cobb points to the tremendous historical richness in King’s writings that goes largely ignored in reporting about King. We rarely hear of the connection King made in his August 1963 speech at the March on Washington with that year’s centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation. We don’t hear of the 1958 voting rights speech “Lessons From History,” given at Galilee Baptist Church in Louisiana, where King talked about what African Americans could learn from history and from struggles of national liberation in Africa and Asia in order to persist in the pursuit of justice.

We will not hear about the tremendous depth of analysis in his last book, “Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?” In that book King identified cultural erasure as a form of racism — and yes, he used the word “racism” — in the miseducation (yes, he used Carter G. Woodson’s famous word) of Black and white children.

King would loudly applaud “The 1619 Project: A New Origin Project” and the struggle of Nikole Hannah-Jones and her colleagues to include the full scope of slavery in the national narrative. King would remind the nation and the world, using the words of W.E.B. Du Bois (someone King celebrated in one of his last speeches in February 1968 at Carnegie Hall), “before the pilgrims landed we were here.”

Despite the media recollections you’ll see on MLK Day, the “I Have a Dream” speech is mislabeled. King opens the speech by talking about an oppressive political economy, directly naming not only discrimination but also poverty as part of the nation’s bankrupt promises. He outlines the long litany of challenges national and local, personal and political, that prompted the march and the necessary continuation of the movement.

Embedded in the speech was a geography of struggle that took seriously the admonitions of the biblical prophets. It’s the voice of Amos we hear when King called for justice to roll down as waters and righteousness as a mighty stream. We heard the voice of Isaiah as King insists that “every valley shall be exalted and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain and the crooked places will be made straight.” What is he summoning if not a transformation of structural foundations?

Calling many of those who had been victims of police brutality and other violence “veterans of creative suffering,” King urged them to redeploy, “go back,” to the battlegrounds of struggle both North and South.

It was Mahalia Jackson who had urged King to insert the poetic testimony of his dream. The focus on this six minutes of his 16-minute speech leaves the entirety of the address romantically misread and undertheorized. In an era where critique of racism is prominent in our discourse, we rarely hear that King’s dream directly labeled segregationists “vicious racists.”

King exhorts his listeners to return to the struggle, using faith and hope as special weapons. He talks about the faith and hope he will take back to the South to “hew out of the mountain of despair, a stone of hope.”

That glancing reference invokes the prophetic-apocalyptic voice of Daniel. In the Book of Daniel, a monarch has a dream so troubling that he demands that his fortune tellers and soothsayers interpret it for him on threat of death. The dream contained a huge idol made of gold, silver, brass, iron and clay. Yet this bright idol is destroyed when “a stone” that was “cut without hands” smashes the idol to pieces.

Daniel, “a man of the captives” in exile — an Israelite — is able to interpret the dream, telling the monarch that after destroying the idol full of unjust power, that stone itself becomes a mountain and fills the land. Enslaved Americans sang of it as “Daniel’s stone-a-rollin’.”

King uses this biblical poetry to offer a vision for an America where freedom rings “from every mountainside,” telling his listeners,“if America would be a great nation this must become true.”

The sanitized dream of Dr. King, with its vision of a colorblind future, misses the inconvenient truths he told in the speech about the nature of change that must take place in America. It is not just the prominent places, but the small places must be changed, where the specific idols of racism and white supremacy reside — “Stone Mountain of Georgia” and “Lookout Mountain of Tennessee” and “every hill and molehill of Mississippi.”

We are still struggling with these same idols nearly 60 years after King challenged the nation to “Let freedom ring.”

RELATED: Remembering Jan. 6 on its ‘anniversary’ is not enough

As we celebrate the birthday of a man who called us all to struggle and to service, the nation still struggles with the challenge of voting rights. We are mourning the loss of major soldiers in this soul force struggle — Episcopal Bishop and apostle of truth and reconciliation Desmond Tutu; voting rights litigator and law professor Lani Guinier; civil rights activist, rebel churchman and desegregation expert Charles Vert Willie; scholar of Black preaching and pioneer of women’s ordination Henry Mitchell; founder of the American Indian Movement Clyde Bellecourt; and actor and committed civil rights activist Sidney Poitier.

They are part of a cloud of witnesses who remind us, in the words of Sen. Jon Ossoff, “We cannot hide from history at this moment.”

My ancestors asked the questions, “Didn’t my Lord deliver Daniel? Why not every [one]?” We must continue to use our tools of faith, hope, courage and love as the special spiritual weapons that God has called us to use so that “all flesh” can see a just and peaceful and equitable world “together” — a world where we truly “lift every voice and sing ‘til earth and heaven ring with the harmonies of liberty.”

Cheryl Townsend Gilkes. Courtesy photo

(Cheryl Townsend Gilkes is the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Professor of African American Studies and Sociology at Colby College; assistant pastor for special projects at Union Baptist Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts; and author of “If It Wasn’t for the Women: Black Women’s Experience and Womanist Culture in Church and Community.” She dedicates this essay to the memory of Deacon Quintus Ervin McDermott (1936-2021). The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)