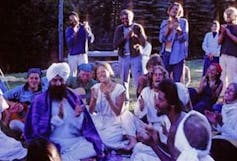

(The Conversation) — Throngs of people, most wearing white clothing and many adorned in traditional Sikh attire, gathered in the Jemez mountains of New Mexico in June 2019. The occasion was the summer solstice. Those who came to celebrate were part of a community started in the U.S. in 1969 by an Indian Sikh man named Harbhajan Singh Puri, who later became known as Yogi Bhajan or Siri Singh Sahib. Puri was a Punjabi Sikh who had worked as a customs agent in India before moving to Canada and then to the U.S. He gained a following while teaching yoga in the U.S.

Puri’s followers formed a community that has spawned a number of organizations since its founding, and although it doesn’t have a single comprehensive moniker, the community is often referred to by two key organizations connected to it: 3HO, which gets its name from the “three H’s” that stand for happy, healthy and holy, and Sikh Dharma International, or SDI. Although the community has acquired members across the world, it remains largely U.S.-based.

Since 2019, the community has not gathered to mark the summer solstice. After a hiatus of three years, 3HO and SDI will once again hold a large-scale summer solstice event in June 2023. This gathering serves as an important opportunity for members scattered across the U.S. and across the globe to meet. As a sociologist of religion, I have spent years researching this community, and I was also raised within it. This gives me a strong sense of the stakes of reopening the annual solstice celebration.

3HO, SDI and the Sikh Panth

Founded in 1969, 3HO is focused on the practice of kundalini yoga. Kundalini yoga uses various postures, chanting and breathing exercises to raise one’s kundalini, a form of sacred energy that some schools of Hindu thought believe rests at the base of the spine.

SDI, formed in 1973, is focused on sharing the Sikh religion as taught by Puri. The Sikh religion is a tradition that originated in India and is often closely tied to an ethnic identity. Within the 3HO and SDI communities as a whole, practitioners often see kundalini yoga and the Sikh religion as bound together, with one being a pathway to the other. Although each organization has a different focus, for members at the core of the community, the practices taught by each aren’t separable in their regular religious and spiritual practice.

The community is made up of mostly converts to the Sikh faith, and practitioners within it have not always been accepted by Punjabi Sikhs. Tensions between them and Punjabi Sikhs stem from a number of differences, which include the practice of kundalini yoga, all-white attire and the reverence often shown for Puri.

In the wider Sikh community, yoga is not typically thought of as a Sikh practice, there is no religious imperative for wearing white clothing, and giving religious reverence to a living figure is largely frowned upon. The summer solstice celebration itself, which is not typically marked by Punjabi Sikhs, is another substantial difference.

Summer solstice and current challenges

The structure of the summer solstice event has varied over the decades, but major elements included a daylong prayer for world peace, yoga classes, meditation and Sikh gurdwara, or temple, services.

Summer solstice has been a time for community members to gather and engage with one another.

Kundalini Research Institute and Teachings of Yogi Bhajan, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

However, until this year, the community had not gathered to mark the summer solstice since 2019. This was partly due to the pandemic but also likely because it has been mired in crises. Since the death of Puri in 2004, a struggle for control of power and community resources followed, though the community largely held itself together.

In 2020, however, allegations of sexual assault and abuse leveled against Puri led many within the community to share additional allegations against other community members and community organizations. In remote meetings open to people connected to the community, some of which I attended, the children of community members also voiced concerns about physical and sexual abuse and neglect they had experienced in schools and camps initially created for children of the community. One example is the school Miri Piri Academy in Amritsar, a city in northern India.

An independent organization set up to investigate the allegations concluded in the fall of 2020 that “it is more likely than not” that Puri engaged in several types of sexual misconduct.

Now, four years since the last large-scale gathering on the summer solstice, the community will once again open Ram Das Puri, a plot of land in the mountains of New Mexico owned by the Siri Singh Sahib Corp., another arm of the community that manages its assets and resources, to mark the summer solstice.

As the community gathers, it will be a time of reckoning with the past. In light of recent crises, attendance at the event may well indicate whether the community still retains a wide enough base to support it.

(Simranjit Khalsa, Assistant Professor of Sociology, University of Memphis. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

![]()

CC BY-NC-SA)" >

CC BY-NC-SA)" >