(RNS) — Early on in Bram Stoker’s “Dracula,” an innkeeper’s wife begs Jonathan Harker, a reasonable British solicitor, to take a crucifix with him on his travels in Transylvania. A good Anglican, Harker, who has “been taught to regard such things as in some measure idolatrous,” accepts the gift out of courtesy. He’s soon whistling a different tune, as the icon repels an attack from Count Dracula himself. “Bless that good, good woman who hung the crucifix round my neck!” he says.

Stoker too was a Protestant, but his novel embedded in the horror genre its fascination with Catholicism and its effectiveness against evil. In their quest to save Mina Murray from Dracula’s seduction, Stoker’s Anglican heroes are on their heels until they meet Van Helsing, the staunchly Catholic Dutch doctor who knows how to use the sacraments to send vampires back to hell. He’s even received a dispensation from the Vatican to crumble consecrated Eucharistic hosts to use the crumbs to ward off vampire attacks.

“When it comes to fighting vampires and performing exorcisms, the Roman Catholic Church has the heavy artillery,” wrote Roger Ebert in his 1998 review of John Carpenter’s “Vampires.” “Your other religions are good for everyday theological tasks, like steering their members into heaven, but when the undead lunge up out of their graves, you want a priest on the case. As a product of Catholic schools, I take a certain pride in this pre-eminence.”

A product of evangelical Christianity, I couldn’t help but be a little jealous. My own spiritual upbringing was rigorous, but there was a reason people in scary movies always took refuge in Catholic cathedrals and not churches with names like First Baptist or The River. Stoker understood that whichever side of the Reformation you vouched your soul to, Catholicism just has more creative oomph. Filmmakers followed suit.

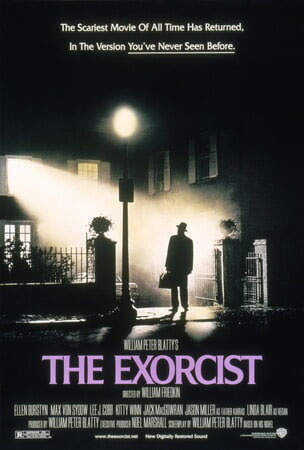

But Ebert’s review was about the last time anyone could say such a thing with a straight face. Catholicism’s pride of place in horror movies, from “The Exorcist” to “The Omen,” came crashing down in 2002, when The Boston Globe’s Spotlight team published its investigation into the Catholic Church sex abuse scandal. Audiences who saw the Oscar-winning 2015 docudrama about the Globe’s hunt for bad priests are understandably less willing to associate priests and nuns with a surefire defense against evil.

It’s arguable that this was the moment that undid Stoker’s work, turning religion from the ultimate defense into the monster itself. Recent television series such as Mike Flanagan’s powerfully spooky “Midnight Mass” show how suspicious horror has become of institutional religion, given how easily adherents can be manipulated.

Nowhere is this evolution more apparent than in “The Conjuring” universe. The movie franchise “inspired” by the “real-life” cases of paranormal investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren has racked up an impressive collection of spooky campfire tales. No matter that the tales’ purported veracity withered under the slightest journalistic prodding — a story doesn’t have to be true to be good — in 2013, director James Wan turned the Warrens’ 1971 investigation of a Rhode Island farmhouse haunting into a real hit. The MPAA famously slapped the deliciously tense nail biter with an R rating not for language, sex or violence, but because it was “just so scary.”

It’s been diminishing returns for the franchise ever since, as a gamut of sequels and spinoffs and sequels to spinoffs mostly failed to capture the same creeping dread. The latest, “The Nun II,” has come closer than most, boasting a sturdier script and more confident scares than its predecessor. It also gives its star, Taissa Farmiga, the freedom to deepen her exploration of her characterization that the last installment didn’t make available to her.

The movie’s Big Bad is Valak, a demon who takes the shape of a creepy nun, twisting objects of piety into horror. He’s the main suspect when a priest dies in a murder that might be charitably described as “suspicious” (he was burned alive while floating in his church in France), and since Sister Irene (Farmiga) tangled with Valak in the first movie, Rome sends her to investigate. Playing Scully to Sister Irene’s Mulder is Sister Debra (Storm Reid), who isn’t so sure about all this “supernatural” nonsense. Her skepticism, suffice it to say, gets put to a powerful test.

The Catholic grounding of “The Conjuring” has always proved fertile. What sets the present subfranchise apart is the way it mines Catholic imagery for austere scares. Nuns here are our heroes, but they are also our demon, and director Michael Chaves has a lot of fun teasing viewers’ mistrust that the next person in a habit won’t as likely drag us to hell as guide us to heaven. Squint a little, and you might see an illustration of how much trust the Catholic Church has lost since the Warrens’ heyday.

This is the central terror of many great horror movies — maybe even most of them: That thing you thought was safe turned out to be the instrument of your destruction. In “Rosemary’s Baby,” Mia Farrow’s dream of motherhood is poisoned and it’s her beloved husband who holds the chalice. In 2017’s clown-in-the-sewer-drain caper “It,” the Losers Club discovers their childhood home is host to a cosmic terror.

Still, it’s rarely been the case that the church doesn’t protect us from the devil, but invites him in. But the new trend, for more than just Catholics, is merely a reflection of reality. In 2000, Gallup found that 28% of Americans had a “great deal” of trust in the church and organized religion, and another 28% had “quite a lot.” This year, both of those numbers have dropped to 16%, and 30% of Americans now say they have “very little” trust in organized religion — more than double the number who said the same in 2000. Institutional religion can only attack so many people before its reputation mutates from savior to monster.

And it’s not just Catholics. Filmmakers, taking notice of evangelicals’ own darkening reputation, have deployed some of movies’ creepiest bogeymen against them. The American version of witchcraft is largely a creation of Protestantism, a fact not lost on Robert Eggers in his wonderful 2015 “The VVitch,” whose Puritan fanaticism is as much of a threat as our title character. Point taken, Eggers.

Why would any filmmaker striving for culture relevance credit the church any longer with the purity sufficient to vanquish evil? Horror gives shape to our real fears, amplifying the quietest whispers in the darkest parts of our heads. “Are you afraid of the Church?” asks “The Nun II.” “You should be.”

It’s worth noting that “The Nun II” does not make Christianity itself into a villain. Valak perverts objects of the faith for his own dark ends, but the faith remains secure. In this movie — as in the minds of many Americans — it is the institution that comes under suspicion, not the nuns.

Christians may be understandably defensive about these portrayals. But we can either protest that they are unfair or we can learn from them, accepting them as testimony instead of lambasting them as propaganda. These wounds might sting but, from a certain perspective, they are gifts too — a call to repentance, and to transformation. Bless the good, good horror movies that hang them around our necks.

(Tyler Huckabee is a writer living in Nashville, Tennessee, with his wife and dog. You can read more of his writing at his Substack. This column does not necessarily reflect the views of Religion News Service.)