A historic Jewish cemetery overlooks Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina. (RNS photo/David I. Klein)

SARAJEVO, Bosnia-Herzegovina (RNS) — When Flory Jagoda, the superstar of Ladino music, died in 2021, it was a wakeup call for Vladimir Mickovic.

Mickovic, a Bosnian musician from Mostar, realized that with Jagoda’s death, the music of Sephardic Jews was in danger of being lost forever. “The Sephardic music and culture, their proverbs and literature, is a part of our culture here in Bosnia and Herzegovina,” Mickovic told Religion News Service.

Last year, he released a tribute album called “Kantikas de mi Nonna,” or “Songs of my Grandmother,” referring to Flory as the “nonna” of the Sephardic musical world. The album is also an attempt to recreate the pre-Holocaust Jewish musical tradition of the western Balkans.

In the West, Jewish music is often associated with Klezmer, the folk music of Central and Eastern European Jews that came to the United States with Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants. But in Spain and across southern Europe, the entirely different music of the Sephardic Jews once thrived.

Though there were much larger Sephardic communities in Turkey and pre-Holocaust Greece, Jagoda, who was born in Sarajevo, became the best-known musician working in the Ladino language and music. Her Hanukkah song, “Ocho Kandelikas” (“Eight Little Candles”) is a modern classic and has been covered by Pink Martini and Idina Menzel.

When Jagoda, named Flory Papo, was born in 1923, Sarajevo belonged to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Sarajevo at the time was known as the “Jerusalem of Europe” for its skyline adorned with the towers of mosques, churches and synagogues. Its population was nearly 20% Jews, most descendants of exiles from Spain at the close of the 15th century who were welcomed to the Balkans, when it was part of the Ottoman Empire.

Flory Jagoda in 2002. (Photo by Tom Pich/Wikipedia/Creative Commons)

Their language, Ladino or Judeo-Spanish, is a mixture of medieval Spanish, Hebrew and Aramaic, peppered with Turkish, Greek and Serbo-Croatian influences, among others.

Music was almost as important a tool in transmitting Sephardic traditions, according to Eliezer Papo, a Sarajevo-born Jew who today leads the Ladino studies program at Israel’s Ben-Gurion University. (Papo said he and Jagoda are not related — or no more than any two people hailing from Sarajevo’s small Jewish community.)

The Bosnian Sephardic musical tradition had its roots in the singing clubs of medieval Spanish synagogues — the karaoke of its day, Papo explained. Jewish men would gather before morning prayer to sing contemporary Hebrew poetry, which fit better with the Arabic musical styles of their time than the biblical psalms used in their liturgy.

Coming to Sarajevo after the Expulsion of 1492, the music continued to evolve. As men continued to sing about religious themes, women addressed everyday life. During Havdalah, the ritual that ends the Sabbath, men would sing traditional prayers in Hebrew followed by women who would sing their own Ladino tunes.

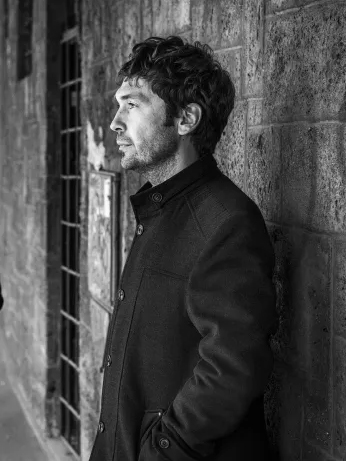

Eliezer Papo. (Photo courtesy Ben-Gurion University)

“In most Sephardic homes, at least once a week, the women would sing,” Papo told RNS.

For Bosnian Jewish women, who before the 20th century had few opportunities for formal schooling, songs were also essential educational tools, transmitting the history, culture and worldview of Sephardic Jewry. “For men, their music gave beauty to life, but for women it imparted wisdom,” Papo said.

Those educational songs and poems were known as Komplas. “There are Komplas about the land of Israel, there are Komplas about Shabbat, about the festivals, about Moses, about Purim, and so on,” Papo told RNS.

In fact, one of the most famous Ladino songs, “Kuando El Rey Nimrod,” which tells the story of the biblical patriarch Abraham, is a Kompla.

Sephardic singers would both give and take from local musical traditions. In Bosnia, that resulted in “Sevdah” or “sevdalinka,” an emotional and melancholic type of folk music that mixes Ottoman and Slavic influences with Iberian and Andalusian tunes brought into the region by Sephardic Jews. Some in Bosnia have argued that Sevdah should be added to UNESCO’s list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Most of Bosnia’s Jews were murdered in the Holocaust, and the few survivors like Flory, who spent much of her adult life in the United States, emigrated soon after the war. The Yugoslav wars of the 1990s led to another wave of emigration from the small community left behind.

Today, fewer than 1,000 Jews remain in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and few of them are involved in musical pursuits.

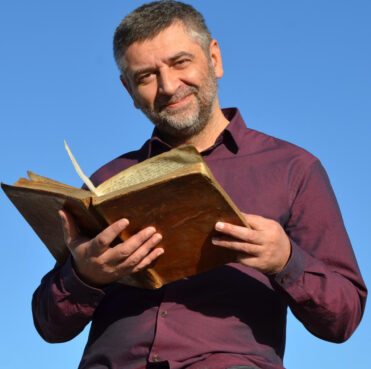

Vladimir Mickovic. (Courtesy photo)

But Mickovic, with the help of a small cadre of other Bosnian musicians, has pieced together an authentic Bosnian sound from Sephardic music from elsewhere in the Balkans. “We went back to those days, the pre-war and after World War era and tried to remember and find materials of how it actually sounded, this traditionally Bosnian Sephardic music,” he said. “But there are actually no recordings, so I found something from Thessaloniki and from Istanbul and so on.”

The final result was an album that traced Flory’s life story and her escape from the Holocaust, which took her from Sarajevo to what is now Croatia and later Italy. But it also tells the whole history of Bosnian Jewry’s trek first from Spain, through Greece and Turkey, to Bosnia and today throughout the world.

Since the release of his Flory album, Mickovic has released several more and is now researching the works of another early 20th-century Jewish composer, this time one from his hometown of Mostar, for a similar tribute album.

Zorana Guja, a musician and ethnomusicologist, has also been researching Sephardic music and its influence on wider Bosnian music. Along with her band, Zorana and the Ethno Orchestra, she produced an album of Balkan Sephardic songs known as “Sephardica.”

For Guja, the lost history of Bosnia’s once-thriving Jewish community, which she said echoed the similar experience of genocide that Serbs faced during World War II, inspired her to undertake the project. “The Sephardic musical tradition had a strong influence on wider Bosnian culture because it managed to merge the musical traditions of both Christian and Muslim populations in urban areas,” Guja told RNS.

If it is forgotten, “Bosnia and Herzegovina will lose not just its vital (Jewish) culture which shaped urban areas and various domains of social life through centuries, but also its Jewish music which is a crucial part of the Bosnian musical tradition as a whole,” Guja said.

For Bosnian Jewry, both at home and beyond, seeing the outpouring of interest in their traditions is welcome news. “It’s an interesting fact that there are many gentiles, more gentiles than Jews basically, who are working to preserve and record these Sephardic musical traditions,” Igor Kozemjakin, the cantor of Sarajevo’s sole synagogue, said. “I feel very proud that it is considered as their heritage by others who are working on this preservation.”

Papo, however, says he isn’t too surprised and traces this interfaith interest in preserving Bosnia’s Jewish culture to the unique Yugoslav brand of socialism that dominated the Balkans for half a century. “In Yugoslavia, you mustn’t forget we were raised with 50 years of socialism when we were taught that everything was everyone’s,” Papo said.

“As a result, any Bosnian musician who wants to sing Bosnian Sephardic songs treats them as his own — and he should, because they are. I am happy about that. Just as his beautiful Mosques are mine, our beautiful Sephardic songs are his.”