(RNS) — I was hanging out with some old friends, and we were reminiscing about the posters that used to hang in our adolescent rooms.

There was the Grateful Dead “Live at the Fillmore” poster. There was a Janis Joplin poster. There were any number of Peter Max posters. And, of course, black light psychedelic posters, complemented by nearby lava lamps.

And then, Dave asked: “Did any of you have that SuperJew poster?”

Ah, yes. Smile. Sigh.

It was the summer of 1967, and Israel had just won a decisive (some would have said miraculous) victory in the Six Day War. Israel defeated the armies of Egypt, Syria and Jordan. For a few minutes in history, Israel was the world’s hero. Israel had refuted the image of the Jew as weakling.

It might be hard for you to imagine this now, but in 1967 I was a scrawny kid. I was the favorite victim of junior high school bullies who enjoyed using antisemitic language to torment me.

During one lunch period during that war, a big, hulking guy — who normally would have knocked the tray out of my hands — approached me and said to me: “Hey, you know what, Salkin? You Jews really can fight, can’t you?”

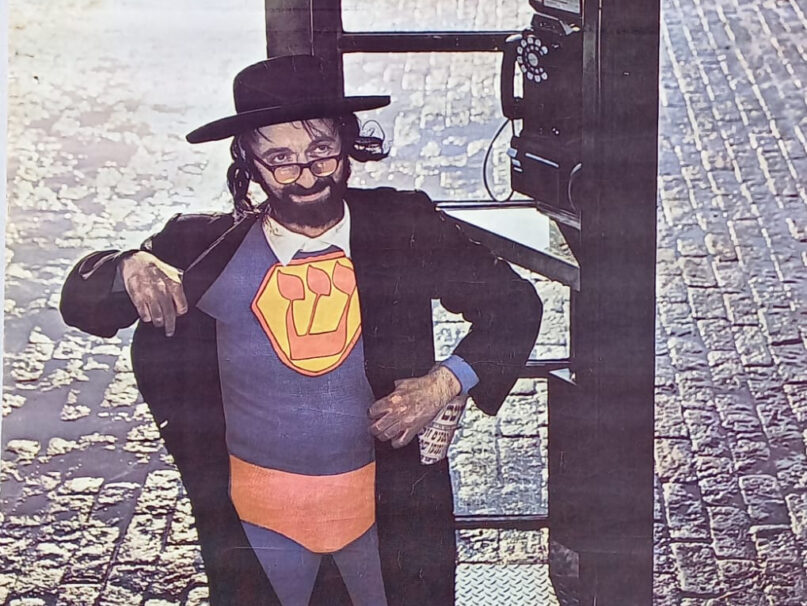

The SuperJew poster created by photographer Harry Hamburg in 1967. (Photo © 1967 Hamburg Studios)

He walked away. My lunch-laden tray remained in my hands.

Israel was my vindication.

During that historic “Israel as heroic” moment, that “SuperJew” poster became very popular. A Hasid emerges from a phone booth, as Superman did in the classic comic. He opens his coat to reveal his costume, with a Hebrew shin on it in place of Superman’s “S.”

There are layers and nuances here. Superman was the creation of two Jews — Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel — as was the entire comic book/superhero industry. Superman first appeared in Action comics in April, 1938, not quite six months before Kristallnacht. It is easy to see how Superman was a projection of the Jewish fantasy for redemption from the emerging Nazi horror.

That poster was a new interpretation of the Superman story. Rather than the reporter Clark Kent going into the phone booth and emerging as Superman, this time it was a Hasid. Journalism was a typical Jewish occupation; piety, in the guise of the bearded Hasid, was a classic Jewish preoccupation.

That poster was a visual representation of a certain version of Zionism. Jews would trade piety for power. They would not wait for God to redeem them; they would do it themselves. This was the Zionist vision of the poet H.N. Bialik, who would view the horrific pogrom at Kishinev, and sneer at the pious men who remained passive in the face of their wives being raped by the hordes. No, said Bialik. It is time to fight back.

But then, as we were reminiscing about the SuperJew poster, I remember how a friend pointed something out to me — more than five decades ago.

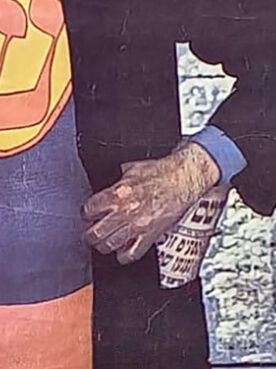

Detail of the SuperJew poster created by photographer Harry Hamburg in 1967. (Photo © 1967 Hamburg Studios)

“Hey,” he said. “Look at his hands! They’re dirty!”

He was right.

Let me offer two distinct interpretations of the Hasid with the dirty hands.

The first is the most obvious: It was antisemitic. It is the image of the Jew as filthy, impure and monstrous.

I have my doubts about that. According to my quick research, the poster was created by Harry Hamburg, Famous Faces, Norristown, Pennsylvania, in 1967.

Who was Harry Hamburg? I don’t know.

But, if we are to assume that Harry Hamburg was Jewish, then the “dirty hands as antisemitic” theory doesn’t quite hold up.

Let’s go for a different interpretation.

It is the “dirty hands as realism” theory.

To have a state, and to defend that state, often means you must abandon the fantasy of purity. It means you have to get your hands dirty.

This was precisely why some Jews originally — and still, today — opposed Zionism. For pious Jews, Zionism was a sullying of the hands; an impure, worldly venture that would prove to be bitul Torah, a waste of time that might otherwise be more productively used for the study of Torah.

Fixing roads, providing utilities, defending a country — feh, who needs it? Better to spend your time in a yeshiva with a study partner, poring over a folio of Talmud.

Some secular Jews did not want to get their hands dirty, either. They also preferred Torah over power — but their Torah was a Torah of ethics and societal critique.

Take, for example, the late critic and literary figure George Steiner. He believed it was the role of the Jews to be a royal pain in the you-know-what. The Jew was to be a “moral irritant and insomniac among men.”

For that reason, the Jew needed to be homeless among the nations. For Steiner, the security of a homeland is a betrayal of Jewish ideals, because the only way the Jews serve humanity as its moral standard-bearers is through societal estrangement.

In both versions of non-Zionism — the pious and the secular, the spiritual goal was clear:

Who may ascend the mountain of the LORD?

Who may stand in His holy place?—He who has clean hands and a pure heart,

who has not taken a false oath by My life

or sworn deceitfully… (Psalm 24: 3-4)

As much as I might respect those versions of anti-Zionism — the “let’s not get our hands dirty” ideology — I must reject them. Both versions, in practice if not intent, sanctify Jewish helplessness and vulnerability.

If I would have said that after the Holocaust, I would say so now, post-Oct. 7. Jewish hands cannot be so clean that they are defenseless against hands that are not only filthy, but stained with Jewish blood.

And yet, an aspirational Zionism means this: Power makes Jewish hands unclean. That is the way of the world.

But, can we at least engage in appropriate, well-placed and well-timed moral critiques of Jewish power? Can we, at the very least, have the desire to wash those hands?

Ultimately, I aspire to live in a world where Hasidic men do not have to emerge from phone booths to reveal super powers. I aspire to live in a world of clean hands and pure hearts.

But, we are not there.

Yet.

(Please enjoy my new book — the first book to outline what a post-Oct. 7 American Judaism will look like — and how we can restore communal obligation to liberal Jewish life. “Tikkun Ha’Am/ Repairing Our People: Israel and the Crisis of Liberal Judaism.”)