VIENNA, Va. (RNS) — The leaves were falling that Saturday in October a year ago. The Halloween skeletons dangled around the front door. Howard Fienberg and his wife, Marnie, were enjoying a lazy morning in their suburban Washington, D.C. home when the phone rang.

It was Howard’s brother, Anthony, calling to tell the couple that there’d been a shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, where Anthony and Howard had attended with their parents growing up. He had just heard it on the news.

The Fienbergs had no doubt Joyce Fienberg was at services that morning. Howard and Anthony’s 75-year-old mother went to synagogue every Saturday — indeed, every day.

The Fienbergs tried Joyce’s cellphone. When she didn’t pick up, they assumed she was busy helping others.

That was typical Joyce.

A consummate volunteer, especially after her retirement and losing her husband in recent years, she cared deeply for everyone she met.

Joyce Fienberg. Courtesy photo

So Howard and Marnie threw some clothes in a bag and got in the car for the four-hour drive to Pittsburgh.

“We quickly determined once we couldn’t reach my mom that we should go and just be supportive,” Howard Fienberg said. “I was under the blindly optimistic assumption that her phone was off and that she left it behind or hadn’t paid attention to it because she was focused on helping other people.”

This weekend the Fienbergs will be back in Pittsburgh to remember Joyce, as they’ve been a dozen times since that awful day of the deadliest attack on Jews in U.S. history. The Tree of Life shooting, which killed 11 and wounded seven, has forever changed the lives of American Jews, who were jolted to discover they were not as safe as they had long assumed.

The Anti-Defamation League reported this week that at least 12 white supremacists have been arrested for alleged roles in terrorist plots, attacks or threats against the Jewish community in the year since the massacre. That includes another shooting in April at a synagogue in Poway, California, that left one worshipper dead and others injured.

As they partake in the Tree of Life anniversary events this weekend — a private get-together with other victim families, a memorial service, Torah study sessions, a community service project — the Fienberg family will contemplate the toll of the tragedy in different ways.

Howard and Marnie Fienberg outside their home in Vienna, Virginia. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

Marnie Fienberg was prompted into activism. She left her job as a federal contractor in communications strategy to start “2 for Seder,” a project dedicated to fighting anti-Semitism by acquainting non-Jews with the Passover story of the biblical flight from slavery to freedom.

READ: Telling the Passover story in the shadow of the Pittsburgh massacre

Howard, 45, a lobbyist for Insights Association, a marketing research trade organization, found himself reinvesting in the traditions of his faith. As a kid, he used to hate going to services at Tree of Life, preferring to ride his bike, watch a hockey game or play with his friends. Now he found himself ever more tethered to the rhythms of synagogue service at his Virginia synagogue, Congregation Olam Tikvah.

“I’m much more involved in my synagogue as a result of this,” Howard Fienberg said. “What route that takes, I don’t know.”

Like many of those affected by the massacre, he is wary about what comes next, but is leaning on the past to guide him forward.

Finding a new mission

Last October, Joyce Fienberg was just emerging from a difficult period of grieving. Two years before, she had lost her mother, her mother-in-law and then Stephen, her husband of 50-plus years.

Fienberg was a caretaker to all three, shuttling between the apartment she shared with Stephen, an internationally acclaimed statistician at Carnegie Mellon University, and her native Toronto, where her mother and mother-in-law both lived.

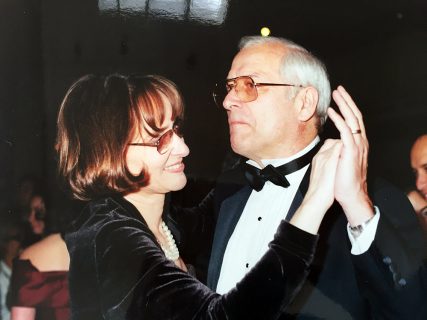

Joyce and Stephen Fienberg at their wedding. Photo courtesy of Howard Fienberg

Joyce and Stephen Fienberg at a family wedding. Photo courtesy of Howard Fienberg

As always, Joyce also managed to fit in some volunteer shifts. She had retired from her job as a research specialist with the University of Pittsburgh’s Learning Research and Development Center, opening up more time for her two primary helping jobs: one with the National Council of Jewish Women, which offers free child care to parents and guardians appearing in court; the other with Family House, an agency that provides temporary homes for patients and their families who are in Pittsburgh seeking medical treatment.

“She was very consistent,” said Marnie Fienberg. “You could always count on Joyce.”

Still in good health, Joyce began going daily to Tree of Life to say kaddish, the mourner’s prayer, for her husband and mother.

After arriving in Pittsburgh in 1980, Stephen and Joyce had attended Tree of Life only occasionally at first, but made sure to enroll their boys in Hebrew school and Sunday school.

A bustling congregation with a membership of 850 families as recently as the 1990s, Tree of Life had struggled more recently to keep up its membership. In 2010, it merged with another congregation, Or L’Simcha. Later, it began renting out parts of the building to other small congregations.

Joyce made it her mission to help revitalize the congregation. She joined the synagogue board and drove 1.5 miles every morning from her home in the Shadyside neighborhood to the synagogue in Squirrel Hill for a brief service in which Jews say a prayer for relatives who have died.

She did this even when she was no longer a mourner, standing in to help make a minyan, or quorum, of 10 Jews, the minimum required by Jewish tradition, to conduct the daily prayers. Often she picked up Moe Lebow, an elderly gentleman who had difficulty driving on his own.

This became a significant part of her life in retirement, and her devotion to the synagogue extended to the most minute details. In the month before the shooting, she told her son and daughter-in-law that the synagogue’s dishwasher had broken. She had been looking for the right part so she could fix it.

That’s why family knew with complete certainty that Joyce was at synagogue on Oct. 27, 2018. The gunman spewing anti-Semitic invectives had stormed into the building carrying three handguns and an AR-15 and shooting indiscriminately.

“We thought she’d be distraught,” said Marnie Fienberg. “And she might need us.”

A framework for mourning

The worst part was the waiting.

After pulling up to Pittsburgh’s Jewish Community Center about 3 p.m., Howard and Marnie Fienberg were ushered into a conference room with other Tree of Life family members to await announcements from the police and FBI about the fate of their loved ones.

Holding candles, a group of girls waits for the start of a memorial vigil at the intersection of Murray Avenue and Forbes Avenue in the Squirrel Hill section of Pittsburgh for the victims of the shooting at the Tree of Life Synagogue. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar)

By 11 that evening, they pieced together enough information from the others in the room to know that Joyce was not among the helpers or injured at the hospital. At 1 a.m., they were summoned by Tree of Life Rabbi Jeff Myers, the medical examiner and the coroner and informed that Joyce was among the victims.

The funeral took place the following Wednesday. The shiva, the seven-day period of mourning in which close relatives sit in the house — in this case, Joyce’s apartment — followed.

Jewish mourning practices were established to offer a gradual set of time frames for reengaging with life. After the shiva, mourners are allowed to resume their lives and go back to work.

Jewish law recommends a 30-day transition period (called the “sheloshim”) for people mourning the death of a parent, and an 11-month period during which Jewish tradition requires children to say the kaddish prayer daily for their dead parents in the company of at least 10 Jews.

“The masoret (or tradition) gives us tools and support to navigate an immediate loss,” said Rabbi David Kalender of Congregation Olam Tikvah in Fairfax, Virginia, Howard and Marnie Fienberg’s synagogue.

In 2016, Howard had gone to Olam Tikvah to say kaddish for his father for about a month, then sporadically. But when Joyce died, he decided he would say kaddish for the full 11 months.

Every day.

Howard Fienberg and his mother, Joyce. Photo courtesy of Howard Fienberg

This meant changing his schedule. Instead of firing up his laptop after dinner to do some more work, he drove 20 minutes to the Conservative synagogue, which held a short daily service at 8 p.m. Like his mother used to do, he carpooled with another mourner who was also saying kaddish for a parent.

“The service is just second nature to me now,” said Howard. “I’ve got enough comprehension and aptitude now that I can be a part of it properly, which I was never able to before. So there are these weird upsides of practices.”

On Rosh Hashana, the Jewish new year, Howard and Marnie visited relatives in Florida and Howard said it first occurred to him how much he liked the synagogue service. He had changed.

Last month, that 11-month period of mourning ended. By Jewish law, Fienberg is no longer a mourner, though he will recite kaddish for his mother annually on the anniversary of Joyce’s death (and, if he chooses, at four other occasions during the year).

“I feel very fortunate to have the support structure but also the process to follow,” Howard said. His mourning, he said, “would have been much worse without that process.”

This weekend, amid all the anniversary events, the Fienbergs will be reminded that they still are very much mourning. In November they will be back in Pittsburgh for the dedication of the Carnegie Mellon Stephen and Joyce Fienberg Chair in Statistics. In December, they will gather in Pittsburgh again for Hanukkah.

And there’s the trial of Robert Bowers, the man accused in the shooting, which is expected to begin late next year, though no date has been set. The Department of Justice announced in August that prosecutors will seek the death penalty.

Howard hasn’t decided if he wants to attend. “Do I want to hear the details?” he asked. “Not particularly.”

His attitude these days defines the rest of his life post-Tree of Life, a one-day-at-a-time approach lined with caution and patience. Or, as he liked to put it: “We’ll see.”