(RNS) — Orthodox Jews are having a moment.

A surge in recent TV shows about Haredi Jews — the ones commonly distinguished by their long black suits and hats, twisted locks of hair (for men) and wigs (for women) — are for the first time competing with shows like “Bridgerton,” “Ted Lasso” and “Hacks.”

It’s a remarkable turnabout for the isolated and highly conservative Jewish communities that, making up just 9% of the U.S. Jewish population, are as obscure to most Jews as they are to most Americans. (The world “Haredi” means one who “trembles” before God.)

The most recent entry to this new golden age of Haredi TV is “My Unorthodox Life,” a reality series about the meteoric rise of Julia Haart from a Monsey, New York, housewife to fashion mogul and CEO of Elite World Group, the global modeling and talent agency.

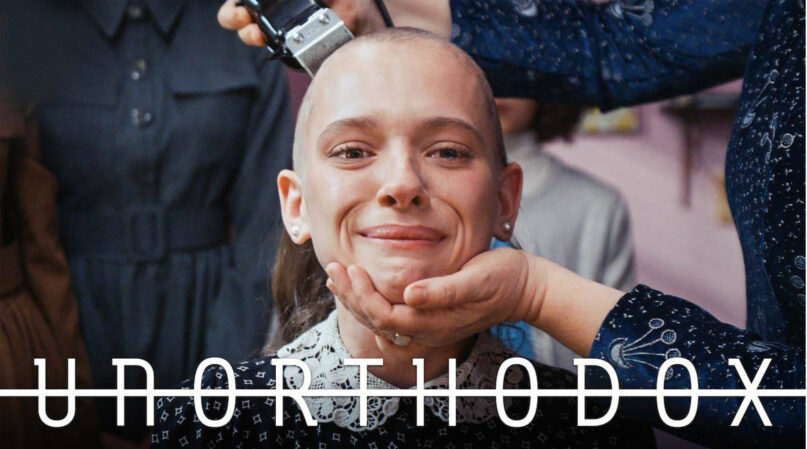

It follows on last year’s wildly successful four-part Netflix series “Unorthodox,” a drama about a woman’s escape from an unhappy arranged marriage in a Brooklyn Haredi community. It won an Emmy for outstanding directing.

Not all these series cast Haredi life in a critical light. Shtisel, a three-season Israeli show about an extended family living in a Jerusalem neighborhood, offers a sensitive, nostalgic and often endearing take on Orthodox life. (It’s not only because it was produced in Israel: Another Israeli production, “Our Boys,” a partially fictionalized account of the 2014 revenge-murder of a Palestinian boy at the hands of three Haredi men, is far more critical.)

A promotional image for “Shtisel.” Image courtesy of Netflix

The question is: Why now?

“There’s been a fascination with these Jews in large measure because in the wider world, they are the last of what looks like recognizable Jews,” said Samuel Heilman, distinguished professor emeritus of sociology at the City University of New York. “Modern Jews don’t stand out.”

RELATED: In voting, Orthodox Jews are looking more like evangelicals

Heilman said the current interest in portraying Orthodox Jews may have begun under former President Trump, whose daughter and son-in-law consider themselves Modern Orthodox Jews (those who make some accommodations to the wider secular world). Many Orthodox Jews rallied to Trump, even as the vast majority of non-Orthodox Jews tilted liberal and supported the Democratic Party.

Orthodox Judaism is also growing. Williamsburg, New York, home to the Haredi Satmar sect, was New York state’s fastest-growing political district, according to the 2020 Census. The New Jersey suburb of Lakewood, which is mostly populated by Haredi, grew fastest of any city in that state.

Being “recognizable Jews” has also brought negative attention: Recently, there has been a spate of violent attacks on Haredi Jews, especially in their New York City enclaves. Anyone wanting to harm them can easily spot Haredi Jews, all the more so since these shows have given them a visual cheatsheet.

Over the past year, too, some of these communities were the subject of news stories for refusing to abide by coronavirus pandemic restrictions.

Orthodox Jews have been represented on film ever since The Jazz Singer, noted Jonathan Sarna, professor of American Jewish History at Brandeis University. In that 1927 classic, a young Jewish man defies the traditions of his Orthodox Jewish father, a cantor in a synagogue, when he takes up jazz.

Sarna said that tradition, which seeks to deal with the tension between Jewish identity and assimilation to American culture, is an old one.

“There’s a whole other group of shows that are trying to reassure American Jews who are not Orthodox: Don’t worry about the growth of Orthodoxy,” said Sarna. “In time they’ll be just like you and me.”

Poster for “My Unorthodox Life” on Netflix. Image courtesy of Netflix

That’s certainly the theme of “My Unorthodox Life,” in which Haart throws off the shackles of her Orthodox life as a mother of four and reinvents herself as a fashion industry entrepreneur with its attendant sexual liberation.

The story of leaving the Orthodox world for the secular one is even older than moviemaking. It’s an Enlightenment narrative, said Shayna Weiss, associate director of the Schusterman Center for Israel Studies at Brandeis University, referring to the 18th-century intellectual movement that emphasized reason and individualism.

One of the oldest narratives in the genre, Weiss said, is “The Autobiography of Solomon Maimon.” Written in 1888, it describes Maimon chafing at the constraints of his rabbinic education in a Lithuanian shtetl and traveling to Berlin where he studied under the German philosopher Immanuel Kant.

Evangelicals, Mormons and Muslims also have their own leaving-the-fold narratives.

What’s really new is that streaming services have begun to take a chance on them, said Shaina Hammerman, associate director of the Taube Center for Jewish Studies at Stanford University.

“We’ve come a long way since the all-white casts of shows like ‘Friends’ were a mainstay of television,” said Hammerman, the author of “Silver Screen, Hasidic Jews: The Story of an Image.”

Shows featuring the leaving-the-fold narrative include the Taiwanese-American sitcom “Fresh Off the Boat” (ABC); the Muslim-American “Ramy” (Hulu) and “We Are Lady Parts” (Peacock); the Indian American “Never Have I Ever” (Netflix); and the Native American “Rutherford Falls” (Peacock), to name only a few.

With the coronavirus pandemic stranding many Americans at home, their appetites for TV shows has expanded their cultural palates.

“There is so much content that creators can afford to take risks and try new types of programming without being afraid of alienating viewers,” Hammerman said.

The one group not watching these shows are Haredi Jews themselves, many of whom do not own TVs and are forbidden from following secular media (though some access streaming services on their smartphones).

Orthodox Jews are aware of a movement known as “off the derech,” meaning “off the path,” to describe those who have left an Orthodox Jewish way of life. The past few years have seen a number of organizations established to help those struggling to enter the secular world after being shunned and ostracized by their families and loved ones. But the subject is not one that consumes them.

“People are aware we are under a microscope,” said Jacob Kornbluh, senior political reporter for the Forward and a member of a Brooklyn Haredi community. “But it’s because we’re different.”

RELATED: ‘My Unorthodox Life’: Meh