(RNS) — Guilt, gender expectations, awkward sexual awakenings, complex family relationships, all in a religious setting: our cultural chroniclers know where to hash out these themes, whether it’s in draconian patriarchal faiths (HBO’s “Big Love”), post-evangelical parodies (“The Leftovers”) or some other post-evangelical or, more likely, Catholic setting.

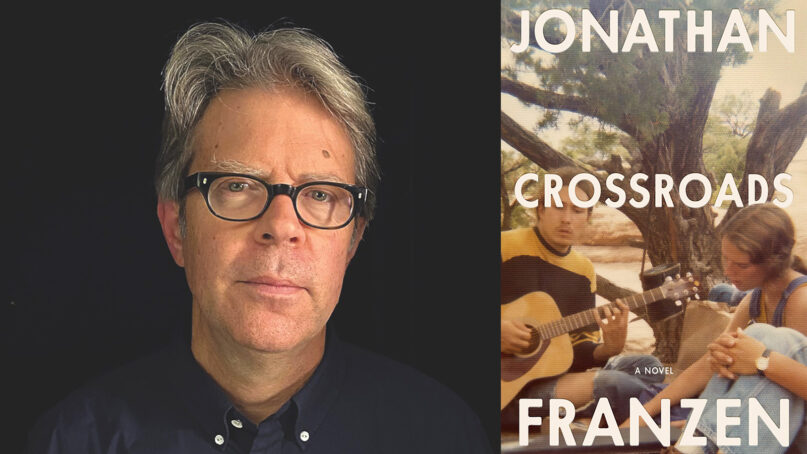

Jonathan Franzen’s new novel, “Crossroads,” finds room for all of this in the story of a clergy family in a liberal Protestant church in the early 1970s, a world rarely explored in fiction in recent years. For those of us who have intimately experienced mainline Christianity as something that is perpetually and irreversibly being diminished, Franzen paints a compelling picture of what liberal, modern church and family life were like in the moments between mainstream Protestantism’s triumphant cultural hegemony and its slow but inevitable decline.

The Rev. Russ Hildebrandt is a middle-aged, mediocre, mid-career associate pastor at the fictional First Reformed Church in Chicago’s west suburbs. The story revolves around the church youth group, named Crossroads, from which Russ is ousted as leader in favor of a younger and cooler staffer who attracts a larger number of teens, including two of Russ’ children, to the group.

The First Reformed congregation and youth group are observed with great care and detail, enough to make veterans of church youth groups wince and laugh. But Franzen’s real achievement is depicting the religious values of a tony white community as the ’60s wind down and the Vietnam War flames out.

“Crossroads” exhibits the emotional intensity and teen hormones of youth groups you may have known, but it deals with it not through prayer and Bible study but conflict-resolution activities, uncomfortable levels of hugging and vaguely spiritualized self help.

Humiliated by his ouster, Russ meanders through his pastoral ministry in the spirit of the age: incorporating elements of Native American spirituality, the pacifist leanings of his Mennonite background and social-service work with a Black church in a different neighborhood.

Russ applies the same awkwardness and earnest self-scrutiny to his romantic longings for a recently widowed younger parishioner, Frances. The complexities of Russ’ marriage to Marion, the most richly developed character in the book, are only slowly revealed, giving Franzen time to treat issues such as teenage drug abuse through the Hildebrandts’ son Perry and to draw a dewy portrait of religious conversion and first love through their daughter, Becky.

But Marion’s backstory is where the novel shows us the realities of how faith works on a person that novels about religion often do not. We also see how abortion, infidelity, mental illness and the cumulative effects of an emotionally difficult and unhappy life play out in the experiences of their spouse and children years later.

Franzen is sometimes as clumsy and unsexy as his characters when it comes to sexual matters. He accurately portrays the guilt and conflict, but, despite the sexually charged era they live in, Franzen’s characters are sexually timid, boring and, we suspect, unskilled. The characters in “Crossroads” transparently idealize conventional female attractiveness: Russ’ crush on the younger and sleeker Frances; Marion’s anguish over her weight; and Becky’s popular-girl prettiness. Even the adolescent son, Perry, offers a judgmental assessment of his sister’s big-boned social rival.

Becky is the only character who gets a vaguely normal experience of sex and falling in love, her sole hang-up being the fact that she’s the preacher’s kid in a liberal church.

Perry and his mother, Marion, are troubled souls. His drug addiction becomes dangerous, as Marion’s psychiatric issues had become years before. The family’s story is so rich that we are left to wonder about the intergenerational transmission of trauma or mental illness. We might understand Russ and Marion better by knowing their parents and grandparents than their children and grandchildren.

But Franzen may shed light by going forward: He imagines “Crossroads” to be the first in a trio of novels that will follow the Hildebrandt family through subsequent generations.

I wonder how much faith will be a part of the next generations’ stories. For me and almost every mainline Protestant kid I grew up with, church was something to graduate from, little knowing how our religious values, texts, music and literature would remain a part of our story long after we left church. Given the expert way he illustrates how faith has an arc in Marion’s or Russ’ lives, it will be fascinating to see how Franzen incorporates it (or its absence) into the next two books.

For now, I am pleased that someone of Franzen’s skill put into relief a faith tradition that was once so baked into the fabric of American life that it was nearly invisible.

When faith is just in the background, it rarely enlivens the choices, conflicts and experiences of men and women as it does in “Crossroads.” But Franzen has done something like what Alice McDermott has done in her novels about northeastern Irish Catholics: richly described not only family dynamics but also a specific religious and cultural context that brings the familiar reader home and compellingly introduces outsiders to something they can begin to understand.

Catholicism has always gotten ample attention in the work of Graham Greene, Walker Percy and Flannery O’Connor. The Protestant literary tradition has gotten a boost with Marilynne Robinson’s “Gilead” trilogy. With “Crossroads” and his forthcoming trio, Franzen has a chance to further elevate the Protestant novel.

The tension in liberal Protestantism has always been whether Christianity accommodates modern culture or transforms it. The practical theological question is how far outside the bounds of revealed, biblical religion and into the experience of the self, the outside world and even sin God might be found.

“Crossroads” shows that Franzen has the ability and perhaps the inclination to give voice to a liberal Christian spirituality with robust experiences and conceptions of God, Christ, sin, grace and redemption. If he keeps going in his next two installments, he will have added to his considerable literary accomplishments.

(Jacob Lupfer is a writer in Jacksonville, Florida. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)